Applications of Clinical Neuropsychotherapy

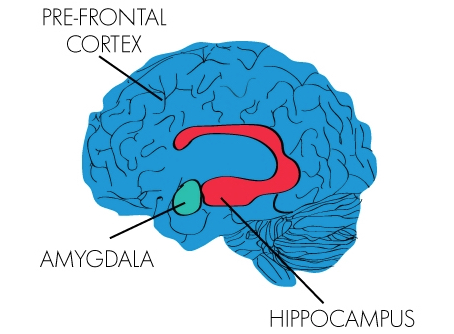

As I intently listened to Professor Rossouw go through the neuropsychotherapy certification coursework material in Sydney back in November of 2016, I noticed that he would get very excited every time he would talk about the hippocampus. The hippocampus is an elegant part of the brain that resembles a sea horse, which resides in the limbic area in dangerous close proximity to the easy to disregulate amygdala. The role of the hippocampus is to provide time and context to our life narrative. Without a properly functioning hippocampus, the human being is trapped and held hostage by the primitive narrative that was created during childhood at a time when the prefrontal cortex could not provide logical analysis of the child’s experiences which in most cases results in children developing narratives that are eschewed towards negative emotions (e.g., guilt, shame). The hippocampus is unable to properly function when a disregulated amygdala results in the release of an excessive amount of stress hormones (Rossouw, 2015).

But what exactly does this mean? Why is the hippocampus so important in mental and emotional health?

I was attending a presentation by Gabor Maté on the topic of addiction and trauma in April 2017 at Santa Clara University. Maté (2000, 2010, 2012) is a world-renowned Canadian physician who specializes in the importance of close relationships as the best prevention against addiction and negative behavior. His work highlights the reality that in the life story of most people with addictions, something happened in the past that does not allow the person to stay in the present moment. This dynamic of being ‘held hostage’ by the past takes away the opportunity for the person to exercise their sense of agency in the present (Maté, 2017).

Tying this back to neuropsychotherapeutic principles, my most important role as a therapist is to assist my clients to downregulate their amygdala in order for the hippocampus to mediate information transfer between the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex so that the client has the ability to know what pertains to the past and what pertains to the present. All of this is done through the establishment of trust and safety, so that the client can then be assisted in building alternative narratives to their existing primitive childhood narrative, which is currently getting in the way of their ability to thrive.

Human beings have a tendency to resemble porcupines in their relational dynamics

When I speak to clients about the importance of integrating all aspects of their life narrative, I use the visual analogy of two porcupines trying to get close to one another. Human beings are not perfect. We all carry our baggage, and that baggage exists mostly because things that happened when we were young were usually taken in and stored in long term memory without the young child first being able to logically and objectively make sense of such experience. The result of this dynamic is the tendency for young children to quickly feel ashamed, bad, inadequate or the more encompassing ‘less than’ very quickly. Children that are able to communicate this discomfort to their parents have a better chance of this normal developmental dynamic being addressed assuming that the parents are able to explore the emotional meaning of such discomfort. The challenge for most parents including very dedicated and loving parents is that our society has not traditionally focused on the emotional world of children. Instead, society directs parents to focus on eliminating bad behaviors through consequences. But that has been drastically changing since the decade of the brain in the 1990s.

Back to our porcupine illustration, as porcupines feel the need to get close to one another, they will inevitably find themselves in a situation in which they will be poked by their partner’s quills. If a person has not been able to integrate all aspects of his life including those which were recorded early in life in the context of negative emotions, the inevitable poking that this person will experience in the present as part of a relationship will most likely instantly activate these negative emotions. In essence, the person will feel the pain and discomfort pertaining to the meaning that the partner’s transgression will instantly elicit. The challenge is that this meaning resides in implicit memory and the person will react to the partner’s actions from the perspective of a young child rather than from the perspective of an adult person that is able to understand where such emotions are coming from. Thus, the person will quickly label the partner’s actions as insensitive, rude, inconsiderate, or worse. This is what I meant earlier on when I stated that people are sometimes held hostage by their past. We grow up and become adults, but our relational dynamics are still those of a young child, and we don’t know this is going on. And since we don’t know this is going on, there is not much we can do about it. The biggest challenge is that society leads us to believe that we have control of our actions when in reality the external stimuli travels ten times faster to the area of the brain focused on survival than to the cortical executive area that is focused on thinking and logic (Rossouw, 2016).

On the other hand, when the person has been able to integrate the totality of his life experiences, he will be able to feel sad, hurt or disappointed by the transgression of the partner, and be able to delay his response enough so that he is able to realize that the boiling rage that he is feeling in the moment has been triggered by the partner, but it pertains to his past. This can only happen when the person received assistance from a parent (when he was a youth) that understood the child’s emotional dynamics or through the support of a therapist as an adult. What is happening here is that this person will be able to manage the negative emotions that reside in the limbic area of the brain with his prefrontal cortex, and will have an opportunity to think before reacting. This is emotional self-regulation, and many adults are unable to do this. This is a process that can only be facilitated by someone else because it involves the activation of areas of the brain whose functioning depends on the interaction with others. These developmental functions are called experience-dependent in developmental neuroscience (Cozolino, 2014) as they will not happen automatically.

It appears that the underlying process underneath most interventions that help clients process early childhood stressful and unpleasant memories utilize the process of memory reconsolidation (Ecker et al., 2013). Memory reconsolidation targets the memories which when stored earlier in the life of the person were accompanied by negative emotions, or were in reality negative in nature. In essence the primitive narrative that was stored early in life is able to be updated to reflect a more objective representation of the facts, something that the child was unable to do in his own. The most important aspect of the memory reconsolidation process is for the person to feel safe. The therapist then elicits the target memory, and works with the client to provide an alternative narrative. The critical component of this process is for there to be a mismatch between the relational dynamics that the client has learned to expect in the context of the memory, and a different and perhaps opposite experience that the therapist is able to provide to the client. My relational approach does not end there. While in some cases, the client would only be able to receive this alternative experience from a therapist, in many cases the client is able to receive such experiences from significant people in his life. I work with the client, so that through their enhanced self-regulation, they are then able to elicit an alternative experience from their loved ones. Self-regulation is the key.

In my work with adults, I apply the Parent Relational & Developmental Neuropsychotherapy Protocol (Veliz, 2017). My job is to initially provide co-regulation for the client, and then help the client orchestrate experiences with their loved ones that will enhanced their regulation. Eventually, the client convinces himself that he is not as bad and damaged as he thought he was. Clients are also fascinated when they discover that in many cases they have been treated in the way that they expected to be treated, and as they change their personal narrative, they show up in the world differently and people implicitly respond in a more positive way. From a relational perspective, my provision of a mismatch experience for the client is a good thing, but permanent healing comes from the client getting this alternative experience from a loved one. The more this happens, the more the client is able to enhance their ability to self-regulate, and the less power his primitive narrative has in the way the client experiences his present relational dynamics.

References

- Cozolino, L. (2014). The Neuroscience of Human Relationships: Attachment and the Developing Social Brain (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

- Ecker, B., Ticic, R., Hulley, L. (2013). A primer of memory reconciliation and its psychotherapeutic use as a core process of profound change. The Neuropsychotherapist, 1: 82-99.

- Maté, G. (2010). In the realm of hungry ghosts: Close encounters with addiction. North Atlantic Books.

- Maté, G. (2012). Addiction: Childhood trauma, stress and the biology of addiction. Journal of Restorative Medicine, 1(1), 56-63.

- Maté, G. (2000). Scattered: How attention deficit disorder originates and what you can do about it. Penguin.

- Maté, G. (2017, April 11). Trauma and Addiction. Distinguished Speaker Series, Graduate Student Association, Counseling Psychology Department, Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA.

- Rossouw, P. J. (2015). Resilience: A neurobiological perspective. Neuropsychotherapy in Australia, 31: 3-8.

- Rossouw, P. J. (2016). Certification Training: Clinical Neuropsychotherapy Practitioner Workbook. Brisbane, AUS: Mediros Pty Ltd.

- Veliz, T. O. (2017). The use of relational neuro-narratives: A parent neuropsychotherapy relational approach to working with young clients. Unpublished Manuscript.