My Motivation

People Systems is a relational & neuro-developmental approach to human dynamics with special focus on the motivation forces that influence the development of emotional well-being, personal growth, and leadership. This approach to human dynamics is multidisciplinary, integrative, systems informed, developmentally focused, and relationally oriented.

I carry out my work through different functions with the goal to empower people to maximize their potential so they can contribute to make the world a better place. To fulfill this mission, I work with people who are responsible for the development of others. I see these people as leaders – whether they are individuals, parents, sports coaches, teachers, or corporate managers. This work takes many forms including the role of psychotherapist, consultant, coach, workshop presenter, educator, motivator, and author. My goal is to reach the leaders of the many societal systems (e.g., families, schools, organizations, corporations), and to help facilitate their development as only when we have been able to create an integrated and cohesive life narrative of our own do we have the experience and perspective to positively influence someone else’s life. My experience has been that when leaders focus on their personal development, all the people who interact with them are affected in a positive way, especially those who depend on them the most. Unfortunately the opposite is also true. When we don’t work on our development, we get worn down and we then communicate our frustrations in the way that we treat others – especially those that we have power over.

My interest in human development started very early in my life while growing up in Panama. I remember listening to the news about fighting related to the Iran-Irak war with my father when I was seven years old and asking him why were people so angry with one another. I remember asking my father what we could do about it, and more specifically what he could do about it to make it stop. When I was fifteen I read the Amazing Results of Positive Thinking by Norman Vincent Peale and How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie, and my life was transformed. I used a special notebook to make notes about what I was learning, and pretty much ended up copying many parts of the books verbatim.

Later as a senior in high school I was introduced to how our unconscious mind creates mechanisms of defense to protect ourselves against what I now call ‘primitive narratives’ – conceptions about oneself, others, and the future that are created during childhood when the prefrontal cortex is not developed enough to apply logic to the intense emotions that are typical in the developing child. I found this fascinating since Westerners (including me for many years) have been socialized to believe that we can ‘will’ ourselves into everything we want since the underlying assumption is that we are in control of our lives, yet in reality awareness of our unconscious processes is something that requires work that does not happen automatically.

I have enough experience in working with people of all ages and backgrounds to have witnessed that people desperately want to thrive. They want to have intimate relationships, contribute to society; and be committed parents, inspiring leaders, and great employees. They want to feel like they did something meaningful with their lives, and they want to feel like they will leave a mark on the world. Yet many of them don’t know how, and they give up – in most cases in an unconscious way.

I don’t believe that it has to be this way…

Early in my college career I started to realize why people give up. I believe that it is related to what I have learned to call a ‘system thing.’ Societal systems (e.g., institutions) are designed for the least common denominator – to help people survive, but not necessarily to help them thrive. Thriving is something that is “experience-dependent.” Experience dependence is an interpersonal neurobiology developmental process through which the more evolved member of a dyad teaches, inspires and role models as part of the normal relational day-to-day pleasurable interactions.

During my first week as a freshman at Iowa State University, I came across an inscription in one of the walls of the student union. It said something close to: “We come to college not so much to learn how to make a living, but rather to learn to live a life.” To me this was a powerful message that meant that just getting a college degree and the best paying job after graduation might result in getting a great paycheck (i.e., survival), but not in having a path towards a sense of fulfillment (i.e., thriving).

I never forgot this inscription and visited it frequently as a source of inspiration during my time at Iowa State. I realized that if I wanted to thrive, I was going to have to actively ‘engineer’ a strategy to achieve this thriving state. Initially, I decided that grades where only part of the story and that I needed to immerse myself in as many leadership activities while shooting for a B+ instead of the perfect A that I had gotten used to in high school. Later on, as a junior I created my own personal development initiative, which I called the Veliz Development Group. My thinking was that I needed to be responsible for my own development. Thus, it wasn’t my teachers’ jobs to prepare me to thrive while I was in college, and after I started working it wasn’t my supervisor’s job to take care of my professional development. To me, it is this sense of ownership of one’s personal and professional development that separates survival from thriving.

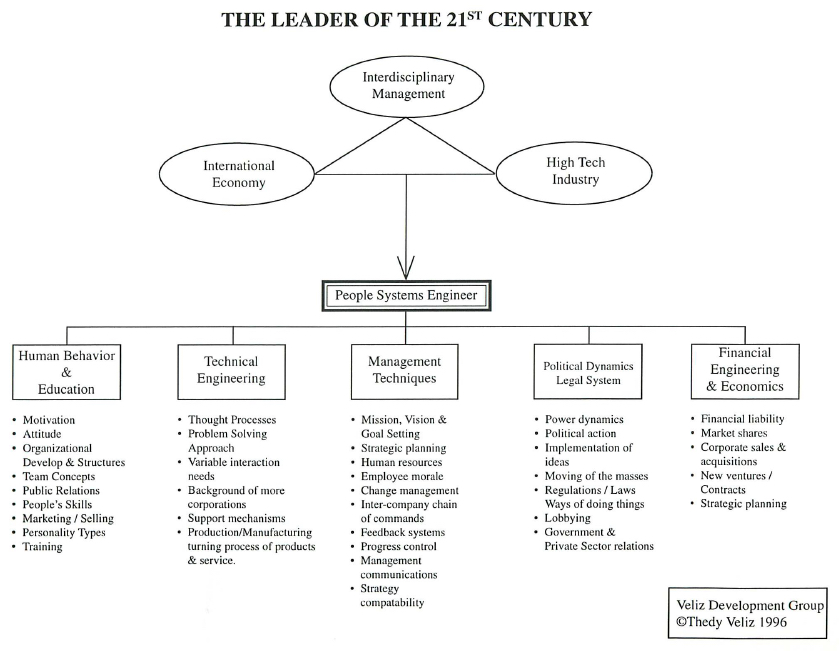

Two years after I started my first job right out of college as a petroleum engineer, I created a roadmap of the skills that I believe I needed to develop in order to be what I called a ‘Leader in the 21st Century.’ I created this document in 1996, and I called this Leader of the 21st century a ‘People Systems Engineer.’

At the time I was driven by success, power, status, and money. As I continued on my journey and my perspective on life expanded, the concept of People Systems started to take on a more comprehensive meaning leading to the development of my relational approach to understanding, healing and enhancing human dynamics.

What type of therapist should I be?

As I was considering enrolling in a masters program in counseling, I took a course offered by UC Berkeley Extension entitled ‘So, you want to be a psychotherapist?’ The course was very informative. It communicated that there were a lot of psychotherapists in California, and most were making less than half of I was making in my corporate finance job. The message that the instructor was trying to communicate was that in order to thrive as a therapist, I needed to have a very good reason to engage in this journey, and I needed to develop a competitive advantage, as this was a very crowded marketplace.

I had taken a sabbatical from the corporate world since I was exploring how to proceed with my life, and now that I did not have the worry about my green card, I had the freedom to focus on what I really wanted to do with my life. Many of my decisions had been informed by my desire to be able to stay in the United States, but I had not forgotten what I had always been very passionate about – the area of personal and leadership development.

I saw becoming a therapist as more than helping people to improve their symptoms. Instead, I saw it as an opportunity to help people see a different way of living – to engage in the world and question their environment. I saw symptoms as people communicating that something was not right not necessarily only with themselves, but also with their environment.

On the first day of my first graduate course in counseling psychology, I realized that the research that I had been doing was directing me to have a different perspective, and this would inevitably challenge my professors. The instructor mentioned that when stress resulted in psychosomatic symptoms it was because people were not well adjusted, and the solution was to assist people in becoming better adjusted. Of course, this teacher’s background was neither in child development nor in neuroscience. However, through my independent research, the way that I saw it was that the symptom was providing information to the person about a possible mismatch between their current environment and their biological needs. It seemed that the symptom was telling the person that perhaps the environment was toxic to the wellbeing of the person. To me, becoming better adjusted would be what I call ‘surviving.’ Exploring why the environment might be affecting the development and functioning of the person would be closer to what I call ‘thriving.’

When I say that I would challenge my professors, I am not saying that I dared to disagree just because… Since I had taken a break from work, I had been becoming familiar with the existing research in every possible field that I could find which was related to individual and collective wellbeing, health, growth, and development. This masters program was not something that I was pursuing because I wanted to make more money. Actually, unless I played my cards right I would most likely make much less money. It was not a degree that I felt that I needed to climb the corporate ladder – I had two of those already, and I felt comfortable in using them to make a good living. This path was different… This program was not about memorizing what the teacher wanted me to know, or about getting the best grades so that I could increase my chances of being sponsored by a company so that I could stay in the United States. This was about addressing those concerns that I had when I was seven years old regarding why people were fighting with each other in the Middle East. I wanted to understand what motivated people to be who they would end up being. This pursuit was very different than everything that I had done before in my life.

My personal project was to understand how being a therapist would contribute to helping people achieve the ability to exercise their own leadership capability – their own sense of agency and self-determination. As I have mentioned elsewhere in this website, I found attachment theory very early in this journey at an Esalen Institute workshop that I attended in 2002. But there was much more… I kept finding different theories, constructs, and research fields. After over ten years of compiling and categorizing findings, I realized that all of this academic, research and clinical work that I was studying told the same story.

When people are exposed to a low-stress environment when they are young, they have a tendency to live more fulfilled and productive lives while contributing to bringing fulfillment to the lives of those around them. The impact of early child development does not only affect the individual, but also the collective. But this is not the entire story… My sense is that most of us were exposed to higher than optimal levels of stress when we were young. This does not necessarily have anything to do with parents. Parents are also people. They get sick and depressed. They die. They have substance use challenges. They loose their jobs. Stress happens to people, and we are not born being biologically equipped to manage this stress when it happens. However, we now know that people are not doomed if they had a less than optimal childhood environment. We now know that the brain is plastic, and this makes me very hopeful and excited. When people are able to receive a treatment that assists them to accept, process, embrace and integrate their adverse experiences, there is something very powerful that happens – people find meaning. They are able to make friends with their less than perfect past, and this integration propels them into engaging in a thriving way of living. I have the privilege to see this transformation take place in my office with my clients.

Increasing Fulfillment Capacity

What I learned is that early low stress environments result in an increased ‘Fulfillment Capacity.’ I started to develop an extensive matrix listing all the different psychological constructs that had been studied, and the results of those studies when there were low levels of stress and when there were higher levels of stress early in life – what the Harvard Center for the Developing Child calls “toxic stress.”

Back to my course ‘So, you want to be a psychotherapist?,’ my competitive advantage as a therapist – what makes me different – is that when I work with a client, the task is not to get rid of the symptom. Instead of seeing the person as having a syndrome, diagnosis, or an ‘issue,’ I see their challenges as a communication that something has gone wrong, and they want to better understand why. This might sound trivial, but it is very challenging to see the good in people when we put ‘diagnostic labels’ on them. The People Systems approach is a leadership educational experience through which the client develops a different way of looking at their life narrative. The symptoms eventually go away. The message is that it was never about the symptoms. The symptoms were just the messenger of a much broader dynamic – a dynamic that had held the client hostage and immobilized for many years.