Applications of clinical neuropsychotherapy to working with youth and parents

“Tantrums are a normal part of human development. What matters is for parents to provide interventions that result in children learning to self-regulate so that they can live healthy and productive lives.”

The shift in the parenting paradigm: Neurobiologically Informed Parenting

Before we could see inside the brain and understand its inner workings as in pertains to child development, parenting, and future adult relationships; our culture developed an approach to dealing with human beings that focused mostly on behaviors and thoughts. It’s not that we ignored emotions; it’s just that we did not know how to handle them. It is easier to pay attention to what we can see and hear (i.e., the child’s behavior and articulation of thought through language) than what requires a very subjective interpretation (i.e., the child’s emotions). We did not know that there is a developmental order that the brain follows and due to this sequence, the emotional centers of the brain are fully developed and mostly (although not fully) functional when the child is born, and the more sophisticated logical and cognitive centers are undeveloped and non-operational at birth (Rossouw, 2017). What this means is that emotions are much more powerful in motivating the behaviors and thoughts of children and the younger the child is, the more powerful emotions are in negatively affecting the child’s ability to function and develop. In addition to this, to make emotions much more difficult to manage; emotions reside in the same part of the brain that is responsible for feelings of safety (Gerhardt, 2004) resulting in children’s tendency towards negative emotions in the interest of survival.

The natural sequence of neurological development

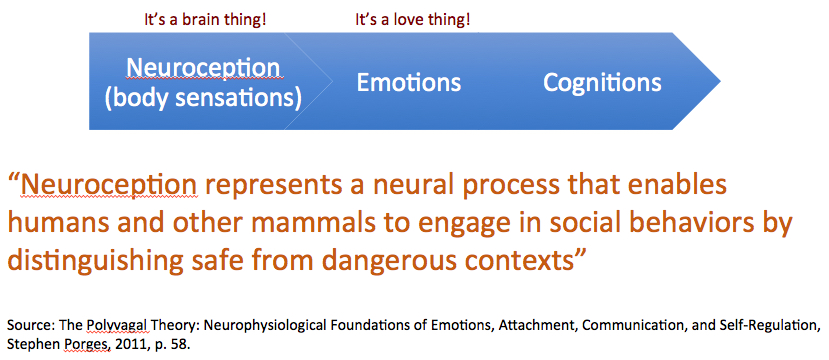

After my weekend seminar in May of 2002 at the Esalen Institute, I became convinced of the importance of parents being mindful of their children’s emotions, however through my clinical practice and ongoing training, it became evident to me that prior to feeling ‘emotions’ as an adult would perceive them, babies are aware of body sensations (e.g., hunger, cold, pain) which are interpreted by the limbic system as a threat to survival.

A baby does not feel sad, angry or worried in the way that a much older child might experience it. Instead, a baby is mostly concerned with what Stephen Porges calls neuroception (Porges, 2011). Neuroception points to a visceral feeling of safety which precedes what eventually become a more emotional feeling of being scared or unsafe which later on can be experienced as a cognitive understanding of feeling scared or unsafe. This developmental progression from neuroception to emotions, and finally cognitions is important in understanding why negative emotions have such a strong ‘veto power’ over positive emotions. Our brain is biased towards safety and survival. The more a parent accommodates this neurobiological developmental reality, the higher the chances that the child will eventually develop strong neural connections between the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex so that the duties of self-regulation are transferred to the prefrontal cortex which in turn will result in a thriving, integrated and resilient neural state.

Parenting approaches that have been passed from generation to generation have traditionally focused on discipline and restraint as the most important parenting outcome, and therefore have been biased toward paying attention to the behavior and words expressed by children without much focus on how emotions and brain development are responsible for such behavior and language expression.

Our historical inability to understand the powerful role of emotions in children being able to follow familial rules and expectations coupled with the historical importance of restraint and order led to parenting becoming driven by the institution of consequences in order to eliminate inappropriate behavior. This appeared to be a good approach, which in many cases acted as a deterrent to such behavior due to the fear of retribution, yet did not address the source of the negative behavior.

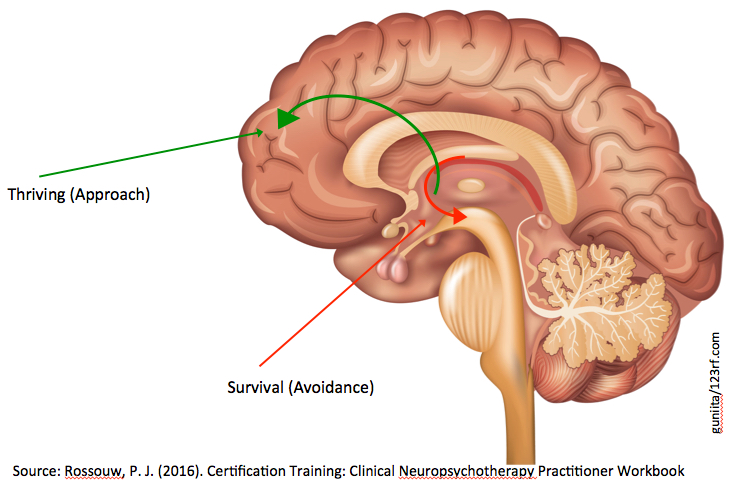

During the first day of my clinical neuropsychotherapy training in November 2016 in Sydney, Professor Pieter Rossouw displayed a very simple powerpoint slide of the brain which put all the pieces of the puzzle together for me. The image pointed to two parts of the brain. The limbic area whose most critical function is the survival of the organism, and the prefrontal cortex which is responsible for our ability to thrive. And here was the message communicated by this slide: If the survival part of the brain is ‘rattled,’ the part of the brain that is responsible for our ability to thrive can’t function. Full stop! In summary if we don’t feel safe, we can’t relate to others, belong to the broader group or function around others. In essence, we can’t love. Thus, when a human being is experiencing behavioral or emotional challenges, something has happened in the child’s history that created an early (primitive) narrative that is now making the person feel unsafe. When we use developmental neuroscience to conceptualize the person’s challenges, it is easy to understand why coping skills won’t be able to solve this problem. Only having an understanding of the current feelings of fear and/or shame, and the integration of the early experiences that resulted in the current dynamic will help the person heal at the source so that the person can move towards a more proactive and resilient way of living.

The entire course was about further developing this concept, and providing clinical approaches to soothe the survival brain so that the person is able to organically move towards utilizing her higher order executive functioning capabilities resulting in a thriving modus operandi.

We need safety before we can interact with others

My experience in 2002 at the Esalen Institute had made me realize that living a Visionary Life – a fulfilling, healthy and successful life – was about relationships. While this is true, what I learned during the first day of my clinical neuropsychotherapy coursework was more comprehensive. Yes, what Robert Mauer called a Visionary Life is about relationships, but only if we feel safe! And this is the key! But it does not end there. The people that are best suited to provide this sense of visceral safety are the child’s parent as parents have two advantages over any therapist.

The first one has to do with the emotional attachment between the child and parent, and even if this attachment has been compromised due to stressful events, children’s development depends on this bond. Thus, even when rejected, children never stop attempting to seek this connection with their parents. Assuming there are no safety concerns, I prefer to guide parents through the process of strengthening and repairing their relationships with their children. And, more importantly, therapists are not able to provide the gentle touch which trigger a cascade of soothing neurochemicals resulting in the downregulation of the amygdala and the increased functioning of the hippocampus and development and strengthening of the uncinate fasciculus, a set of fibers which connects the hippocampus with the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex in order to provide the “context of time and place” (Baylin & Hughes, 2016, p. 147). When the hippocampus is able to provide the context of time and place to memories that might be elicited in the present, the person is able to have the freedom to live in the present while being aware that a current experience might be triggering a past implicit memory. The inability for adults to provide parenting interventions that soothes the amygdala results in corrosive stress hormones negatively affecting the ability for the hippocampus to properly function (Rossouw, 2015).

As a therapist, it became clear to me that the symptoms pertaining to the many diagnoses that are listed in the Diagnostics & Statistics Manual are the behavioral, cognitive and emotional manifestations that come about when human beings do not feel safe. And this makes sense since even when we adults become stressed; we have a tendency to focus on ourselves leaving fewer resources to be concerned with our relationships with others.

In a nutshell, the most important job of all caregivers involved in supporting the growth and development of a child is to facilitate the healthy development of the child’s stress response system. The only way that this can happen is for our interventions with children to always default to help the child soothe their emotions, as they are unable to carry out this function on their own. I have learned in my clinical practice that the symptoms that result in a parent seeking the support of a therapist are related to a dysregulated stress response system which affects the child’s ability to learn, pay attention, follow direction, empathize, relate with others, while giving and receiving love.

Childhood is a time when the human brain is being exposed to environmental experiences, which interact with our unique genetic material. It is this interaction between environment and genetic genotype through the process of epigenetics which results in the expression of our phenotype – the way in which our organic processes will develop and grow to sustain our life (Cozolino, 2014; Peckham, 2013).

Negative behavior as a normal component of healthy behavior

Based on my clinical experience and neuroscience research, I have learned to interpret children’s negative behaviors as a necessary part of human development. The child’s development is highly enhanced when parents understand that how they respond to these negative behaviors will determine if these behaviors endure or not. In a nutshell, responding with interventions that soothe the survival part of the brain will directly contribute to the child’s brain being able to develop stronger and more prolific connections between the survival part of the brain and the executive function part of the brain in the prefrontal cortex. If the parent’s intervention results in the child not feeling safe, parenting has in essence made the survival part of the brain more unstable resulting in the release of stress hormones which are corrosive to the development of the neural networks needed for the child to eventually be able to self-regulate his feelings and not throw a tantrum (Baylin & Hughes, 2016). In summary, consequences work against the desire of the parent for the child to eventually be able to control his outbursts because consequences increase the disregulation of the primitive parts of the brain. Telling the child to chill, explaining to the child why he should chill, threatening the child with a consequence, and/or giving the child a consequence will all work against what the parents wants to accomplish. We didn’t have the research findings to know this in the past, but we do now…

Consequences from a Relational Neuro-Psychotherapeutic Perspective

“... consequences work against the desire of the parent for their children to eventually be able to control their outbursts because consequences increase the disregulation of the primitive parts of the brain. Telling the child to chill, explaining to the child why he should chill, threatening the child with a consequence, and/or giving the child a consequence will all work against what the parents wants to accomplish. We didn’t have the research findings to know this in the past, but we do now…”

Today, most parents know that consequences do not eliminate the negative behavior, yet believe that if a consequence is not given, the child would then learn that their behavior is sanctioned by the parent. Parents feel that if they are not able to give a consequence to their children, they can’t be an effective parent.

As a clinician I have encountered this consequences challenge many times. Initially, my approach was to redirect parents to focus on their relationship with their children as my object relations and attachment theory training and research had taught me that healing happens in relationships. But parents felt like 'a fish out of the water' without having consequences as a parenting tool. At the time, I could not show them why consequences were working against their parenting goals.

Based on the research findings that started to be aggregated by the interpersonal neurobiology movement in the 1990s along with the knowledge acquired through new brain imaging technologies, I now assist parents in implementing a brain-based definition of consequences. While attending Daniel Hughes’ Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy Level I training in August 2015 in Annville, Pennsylvania I joined in with other clinicians as they pushed Hughes to provide some guidance on the role of consequences as a parenting intervention. After attempting to redirect the clinicians’ concerns towards helping the parents to focus on developing, strengthening and maintaining healthy relationship with their children instead of adopting a punitive stance, Hughes stated that a consequence is a parenting intervention through which the parent provides what the child needs to improve his sense of safety and overall functioning (D. Hughes, personal communication, August 4, 2015).

When a child is having a tantrum, this signals the parent that the child has maxed out his capacity for managing his environment on his own and needs the support of the parent. Daniel Siegel talks about parents needing to lend their prefrontal cortex to their children when their children are not able to function because they are lacking a fully developed prefrontal cortex (Siegel & Bryson, 2011). When children become disregulated, the parenting response that will enhance the child’s healthy development is 'time in' instead of 'time out.' Only through loving and soothing parenting interactions is the survival part of the brain down-regulated due to hormones such as oxytocin that are released during such parenting interactions especially if low intensity stimulation of the skin through touch is possible (Uvnas-Moberg et al., 2015).

During an all day session at the 2014 Child Trauma Conference in Melbourne organized by the Australian Childhood Foundation, Daniel Hughes provided additional evidence as to why children need ‘time in’ instead of ‘time out’ when feeling disregulated. Hughes cited research by Jim Coan at the University of Virginia (Coan, 2006; Coan et al., 2010), which highlighted that the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is the area of the brain needed for implementation of coping skills, however this area develops much later in life. It is fully developed in women by about age 22, and in men by about age 28. And… the DLPFC develops much slower in children that have experienced stress early in their lives. In addition, the DLPFC is a ‘high maintenance area’ and because of this its abilities deplete quickly. Therefore, children can only use his self-control capabilities for 30-45 minutes. After this, their abilities to self-regulate, focus, and manage their anger are limited and severely compromised. The most important information that Hughes provided was that because the DLPFC is a highly specialized area, it is not very efficient when the child is left alone. Interestingly, when the child is in the company of a caregiver that provides a sense of safety and security, the child will be using one-third of the capacity of his DLPFC, which means that he will be able to exert self-control three times longer than if he were alone. Hughes concluded that when it comes to a child’s ability to self-regulate, ‘two heads are better than one’ (Hughes, 2014).

Thus, I have developed a protocol which I use with all my clients (e.g., children, adults, couples) that focuses on the self-regulation of the higher functioning member of the dyad and the co-regulation of the lower functioning by the higher functioning member of the dyad. Both of these components are required for the self-regulation of the lower functioning member to eventually emerge. The therapeutic relationship acts as the conduit and catalyst for the regulatory processes mentioned above which is the healing ingredient. Thus, clients heal when a healthy relationship is facilitated between them and the significant people in their lives by the therapist, and not so much by the therapist working with the client, but rather by inviting the client’s significant people into the client’s treatment. This is what I mean by being a relational therapist.

This relational neuro-therapeutic protocol was inspired by using parent therapy (Jacobs & Wachs, 2002; Wachs & Jacobs, 2006) in order to help children improve their symptoms by working with and through their parents.

I presented this protocol in May 2017 at the International Conference of Neuropsychotherapy in Brisbane, Australia. Based on the success of this presentation, I have been invited to deliver a keynote and run a mini-workshop in May 2018 at the 2nd Annual International Conference of Neuropsychotherapy, which will take place in Melbourne, Australia.

References

- Baylin, J. & Hughes, D. A. (2016). The neurobiology of attachment focused therapy: Enhancing connection and trust in the treatment of children and adolescents (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

- Coan, J. A. (2010). Towards a neuroscience of attachment. In J. Cassidy & P. Shaver (Eds.), Attachment Handbook, second edition (pp. 241-265). New York, USA: The Guilford Press.

- Coan, J. A., Schaefer, H. S., & Davidson, R. J. (2006). Lending a hand social regulation of the neural response to threat. Psychological science, 17(12), 1032-1039.

- Cozolino, L. (2014). Experience-dependent plasticity: The science of epigenetics. The Neuropsychotherapist. 1 (5) Apr-Jun 2014, 40-53.

- Hughes, D. A. (2014, August 4). Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy: A relationship based intervention for traumatized children and their families. Masterclass presented by Kim Golding and Daniel Hughes at the Child Trauma Conference, Australian Childhood Foundation, Melbourne, Australia.

- Hughes, D. (2015, August 4). Training Class: Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy, Level 1, Quittie Glen, Annville, PA (Aug 4-7, 2015).

- Jacobs, L., & Wachs, C. (2002). Parent therapy: A relational alternative to working with children. C. Wachs (Ed.). Jason Aronson Incorporated.

- Peckham, H. (2013). epigenetics: the dogma-defying discovery that genes learn from experience. international journal of neuropsychotherapy, 1, 9-20.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

- Rossouw, P. J. (2015). Resilience: A neurobiological perspective. Neuropsychotherapy in Australia, 31: 3-8.

- Rossouw, P. J. (2017). The Neuropsychotherapy Institute Online Training. Course C01 – The Triune Brain [online video]. Retrieved from http://neuropsychotherapyinstitute.com on 4/16/17.

- Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2011). The whole-brain child: 12 revolutionary strategies to nurture your child's developing mind. Delacorte Press.

- Uvnäs-Moberg, K., Handlin, L., & Petersson, M. (2015). Self-soothing behaviors with particular reference to oxytocin release induced by non-noxious sensory stimulation. Frontiers in psychology, 5, 1529.

- Wachs, C., & Jacobs, L. (Eds.). (2006). Parent-focused child therapy: attachment, identification, and reflective functions. Jason Aronson.